Golden Oyster Mushrooms Go Wild: Invasive Fungi Now in 25 U.S. States—and Counting

Once a trendy home grow kit, now a forest invader: new studies show golden oysters are outcompeting native fungi—and that’s just the beginning.

You’ve probably seen them in a trendy mushroom risotto recipe or sprouting from a DIY grow kit: golden oyster mushrooms—those bright yellow, fan-shaped fungi that look as if they belong on an alien planet.

They’re pretty. They’re edible. They’re easy to grow.

But here’s the twist: golden oysters are now invading North American forests—and changing the very fabric of native ecosystems.

From Kitchen Hobby to Ecological Headache

Originally from eastern Asia, Pleurotus citrinopileatus became a popular cultivation species in the early 2000s. Home mushroom kits featuring golden oysters made them easily accessible to anyone with a shady shelf and a spray bottle.

But mushrooms spread through spores—millions of them, so small and light they float on air. It didn’t take long for these spores to escape into local forests.

Now, golden oyster mushrooms have been recorded in 25 U.S. states and at least one Canadian province. They’re spreading fast—and they’re not playing nice with native fungi.

The Wisconsin Study: A Fungal Red Flag

A research team from the University of Wisconsin–Madison recently studied what happens when golden oysters take hold in the wild.

Their findings were unsettling:

- Logs colonized by golden oysters hosted half as many native fungal species.

- Important species like the mossy maze polypore, elm oyster, and Nemania serpens were often absent.

- The native fungi pushed out weren’t just background noise—they’re critical to decomposition, carbon cycling, and even pharmaceutical research.

These aren’t just mushroom battles in the woods—they’re disruptions to forest health.

Why Fungal Diversity Matters

Most people think of fungi as either food or mold. But in forests, fungi are the hidden workhorses:

- They break down dead wood, returning nutrients to the soil.

- They form symbiotic relationships with trees, helping them absorb water and minerals.

- Some even sequester carbon, playing a role in slowing climate change.

When one aggressive species like golden oyster dominates, those systems break down. And with warmer, wetter conditions predicted for much of North America, the problem could grow worse.

This Isn’t Just a U.S. Problem

Golden oysters have now been reported in Europe and Africa too. Genetic analysis suggests there were multiple introductions of the same cultivated strain—not just one accident.

And since these mushrooms are still widely sold online and in garden centers, the risk of further spread remains high.

What We Can Do

There’s no turning back time—but there are steps to reduce the damage:

- Avoid outdoor kits: Only grow golden oysters in controlled indoor settings.

- Dispose carefully: Don’t toss spent grow blocks into compost—those spores are survivors.

- Educate growers and hobbyists: Many don’t realize they’re releasing an invasive species.

- Support fungal monitoring: Apps like iNaturalist let citizen scientists help track the spread.

- Develop safer strains: Some companies are experimenting with sporeless golden oyster varieties—a smart move.

My Take

We tend to think invasives are things with legs—feral cats, jumping worms, zebra mussels. But fungi can be invaders too. And unlike animals, they spread quietly, invisibly, on the wind.

Golden oyster mushrooms are a great reminder that what we grow in our homes doesn’t always stay there. Sometimes, it walks out the door—or floats—and starts rewriting the ecological script in a local forest.

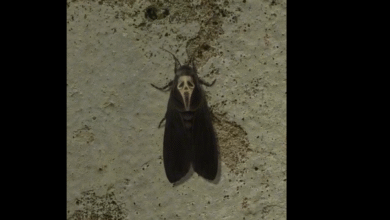

Next time you spot a cheerful yellow cluster on a log, take a second look. It might not be as harmless as it seems.